INVESTIGATION OF THE ASSASSINATION

OF PRESIDENT JOHN F. KENNEDY

APPENDIX TO

HEARINGS

BEFORE THE

SELECT COMMITTEE ON ASSASSINATIONS

OF THE

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

NINETY-FIFTH CONGRESS

SECOND SESSION

VOLUME XI

THE WARREN COMMISSION

CIA SUPPORT TO THE WARREN COMMISSION

THE MOTORCADE

MILITARY INVESTIGATION OF THE ASSASSINATION

MARCH 1979

Printed for the use of the Select Committe on Assassinations

U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

WASHINGTON : 1979

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office

Washington, D.C. 20402

Stock No. 052-070-04981-2

Page ii

SELECT COMMITTEE ON ASSASSINATIONS

LOUIS STOKES, Ohio, Chairman

RICHARDSON PREYER, North Carolina SAMUEL L. DEVINE, Ohio

WALTER E. FAUNTROY, STEWART B. McKINNEY, Connecticut

District of Columbia CHARLES THONE, Nebraska

YVONNE BRATHWAITE BURKE, HAROLD S. SAWYER, Michigan

California

CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut

HAROLD E. FORD, Tennessee

FLOYD J. FITHIAN, Indiana

ROBERT W. EDGAR, Pennsylvania

Subcommittee on the Subcommittee on the

Assassination of Assassination of

Martin Luther King, Jr. John F Kennedy

WALTER E. FAUNTROY, Chairman RICHARDSON PREYER, Chairman

HAROLD E. FORD YVONNE BRATHWAITE BURKE

FLOYD J. FITHIAN CHRISTOPHER J. DODD

ROBERT W. EDGAR CHARLES THONE

STEWART B. McKINNEY HAROLD S. SAWYER

LOUIS STOKES, ex officio LOUIS STOKES, ex officio

SAMUEL L. DEVINE, ex officio SAMUEL L. DEVINE, ex officio

(II)

Contents

Page iii

CONTENTS

Page

Foreword . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . v

The Warren Commission . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Analysis of the support provided to the Warren Commission by the Central

Intelligence Agency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 471

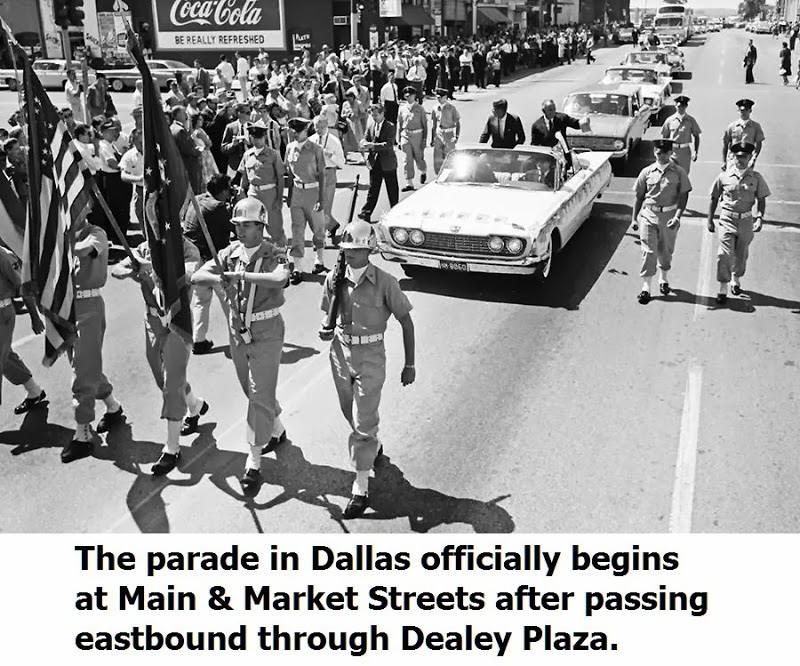

Politics and Presidential protection: The motorcade 505

Possible military investigation of the assassination 539

(III)

Foreword

Page v

Foreword

(1)* During the course of its investigation, the committee conducted an

extensive examination and evaluation of the Warren Commission's investigation of

1964 and final report. As the most authoritative document ever produced on the

assassination of President Kennedy, the Warren Commission report stands as the

assassination must be weighed.

(2) The committee carefully examined the work of the Warren Commission, its

structure and operations, conclusion-drawing process, and production of a final

report. This staff report is in two parts. The first addresses the operations

and performance of the Commission. The second looks at the Commission's

relationships with the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Central

Intelligence Agency.

(3) The Commission's report sets forth the testimony of various key members of

the Warren Commission staff, as well as those members of the Commission who were

still living at the time of the committee's investigation. The former members

and staff of the Commission have, by and large, refrained from any substantive

comment on their past work on the Commission, during the 15 years since their

investigation took place. The following staff report based primarily upon their

testimony, sets forth a review and narrative of the Commission's work by those

most familiar with it at the time.

---------------------------

(v)

The Warren Commission

Page 1

THE WARREN COMMISSION

Staff Report

of the

Select Committee on Assassinations

U.S. House of Representatives

Ninety-fifth Congress

Second Session

March 1979

(1)

Contents

Page 2

CONTENTS

Paragraph

I. Operations and procedures --------------------------------------- (4)

Creation of the Warren Commission ------------------------------- (4)

Purposes of the Warren Commission ------------------------------- (22)

Organization of the Warren Commission --------------------------- (44)

Independent investigators --------------------------------------- (59)

Communication among the staff ----------------------------------- (71)

Interaction between the Warren Commission and the staff --------- (74)

Pressures ------------------------------------------------------- (88)

II. Relationship with the Central Intelligence Agency and the Federal

Bureau of Investigation:

A. Perspective of the Warren Commission:

Attitude of the Commission members ----------------- (113)

Attitude of the Commission staff ---------------------- (144)

Predispositions regarding the agencies -------------- (144)

Attitude of the staff toward the investigation ------ (152)

Initial staff impressions of the agencies ----------- (160)

Attitude of the staff during the course of the

investigation -------------------------------------- (163)

Dependence on the agencies: Staff views ------------- (183)

B. Attitude of the FBI and the CIA toward the Warren Commission:

General attitude -------------------------------------- (188)

The FBI ----------------------------------------------- (188)

The CIA ----------------------------------------------- (205)

Examples of attitudes and relationships --------------- (216)

Introduction --------------------------------------- (216)

Inadequate follow-up --the Odio-Hall incident ------ (218)

Unreasonable delays -------------------------------- (228)

Misleading testimony ------------------------------- (238)

Withheld information ------------------------------- (240)

Attachment A: The Warren Commission ---------------------------- (278)

Attachment B: Monthly progress of the Warren Commission

investigation ------------------------------------------------- (279)

Attachment C: Days worked by Warren Commission staff--1964 --(280)

Attachment D: Transcript of the executive session testimony of Arlen

Specter, W. David Slawson and Wesley Liebeler before the House Select

Committee on Assassinations, November 8, 1977 ----------------- (281)

Attachment E: Transcript of the executive session testimony of W. David

Slawson and Wesley Liebeler before the House Select Committee on

Assassinations November 15, 1977 --------------------------------- (282)

Attachment F: Transcript of the executive session testimony of Judge

Burt W. Griffin and Howard P Willens before the House Select

Committee on Assassinations November 17, 1977 --------------- (283)

Attachment G: Transcript of the executive session deposition of J. Lee Rankin by

the House Select Committee on Assassinations,

August 17, 1978 ----------------------------------------------------- (284)

Attachment H: Transcript of the depostion of Howard P. Willens by

the House Select Committee on Assassination, July 28, 1978 ---- (285)

Attachment I: Letter and attachments from Judge Burt W. Griffen

to G. Robert Blakey, November 23, 1977 --------------------------- (286)

Attachment J: Letter from Howard P. Willens to G. Robert Blakey,

December 14, 1978 ---------------------------------------------------- (287)

(2)

Operations and Procedures

Page 3

I. OPERATIONS AND PROCEDURES

CREATION OF THE WARREN COMMISSION

(4) On November 22, 1963, President Kennedy was assassinated and Vice President

Johnson became President. President Johnson was immediately faced with the

problem of investigating the assassination. On November 23, 1963, J. Edgar

Hoover forwarded the results of the FBI's preliminary investigation to him. This

report detailed the evidence that indicated Lee Harvey Oswald's guilt. (1) On

November 24, 1963, Hoover telephoned Presidents Johnson aide Walter Jenkins and

stated:

The thing I am concerned about, and so is Mr. Katzenbach* is having something

issued so we can convince the public that Oswald is the real assassin. Mr

Katzenbach thinks that the President might appoint a Presidential Commission of

three outstanding citizens to make a determination. I countered with a

suggestion that we make an investigative report to the Attorney General with

pictures, laboratory work, and so forth. Then the Attorney General can make the

report to the President and the President can decide whether to make it public.

I felt this was better because there are several aspects which would complicate

our foreign relations, if we followed the Presidential Commission route. (2)

(5) Former Attorney General Katzenbach told the committee* that there were a

number of factors that led to his belief that some kind of statement regarding

the absence of a conspiracy should be issued without delay. Katzenbach recalled:

I think*** speculation that there was conspiracy of various kinds was fairly

rampant, at that time particularly in the foreign press. I was reacting to that

and I think reacting to repeated calls from people in the State Department who

wanted something of that kind in an effort to quash the beliefs of some people

abroad that the silence in the face of those rumors was not to be taken as

substantiating it in some way. That is, in the face of a lot of rumors about

conspiracy, a total silence on the subject from the Government neither

confirming nor denying tended to feed those rumors. I would have liked a

statement of the kind I said, that nothing we had uncovered so far leads to

believe that there is a conspiracy, but investigation is continuing; everything

will be put out on the table.(3)

----------------------

(3)

Page 4

4

(6) Katzenbach further stated:

I had numerous reports from the Bureau of things that were going on. Again, I

cannot exactly tell you the time frame on this, but there were questions of

Oswald's visit to Russia, marriage to Marina, and the visit to Mexico City, the

question as to whether there was any connection between Ruby and Oswald, how in

hell the police could have allowed that to happen.

Those were the sorts of considerations at least that we had during that period

of time, I guess. The question as it came along as the result of all those

things was whether this was some kind of conspiracy, whether foreign powers

could be involved, whether it was a right-wing conspiracy, whether it was a

leftwing conspiracy, whether it was the right wing trying to put out the

conspiracy on the left wing or the lef wing trying to put the conspiracy on the

right wing, whatever that may have been.

There were many rumors around. There were many speculations around, all of which

were problems. (4)

(7) Deputy Attorney General Katzenbach also indicated his desire to have

"everyone know that Oswald was guilty of the President's assassination."(5) On

November 25, 1963, Katzenbach write a memorandum to Presidential aide William

Moyers in which he stated:

It is important that all of the facts surrounding President Kennedy's

assassination be made public in a way which will satisfy people in the United

States and abroad. That all the facts have been told and that a statement to

this effect be made now.

1. The public must be satisfied that Oswald was the assassin; that he did not

have confederates who are still at large; that the evidence was such that he

would have been convicted at trial.

* * * * * * * * * *

3. The matter has been handled thus far with neither dignity nor conviction;

facts have been mixed with rumor and speculation. We can scarcely let the world

see us totally in the image of the Dallas police when our President is murdered.

I think this objective may be satisfied and made public as soon as possible with

the completion of a thorough FBI report on Oswald and the assassination. This

may run into the difficulty of pointing to inconsistency between this report and

statements by Dallas Police offcials; but the reputation of the Bureau is such

that it may do the whole job. The only other step would be the appointment of a

Presidential commission of unimpeachable personnel to review and examine the

evidence and announce its conclusion. This has both advantages and

disadvantages. I think it can await publication of the FBI report and public

reaction to it here and abroad.

I think, however, that a statement and the facts will be

Page 5

5

made public property in an orderly and responsible way; it should be made now;

we need something to head off public speculation or congressional hearings of

the wrong sort.(6)

(8) Recalling that memorandum, Katzenbach stated:

Perhaps I am repeating myself, but everybody appeared to believe that Lee Harvey

Oswald had acted alone fairly early. There were rumors of conspiracy. Now,

either Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone or he was part of a conspiracy, one of the

two, or somebody else was involved.

If he acted alone and if that was in fact true, then the problem you had was how

do you allay all the rumors of conspiracy. If he, in fact, was part of a

conspiracy, you damned well wanted to know what the conspiracy was, who was

involved in it, and that would have given you another set of problems.

The problem that I focused on for the most part was the former one because they

kept saying he acted alone. How do you explain? You have to put all of this out

with all your explanations because you have all of these associations and all of

that is said, you put out all the facts, why you come to that conclusion. I say

this because the conclusion would have been a tremendously important conclusion

to know.

If some foreign government was behind this, that may have presented major

problems. It was of major importance to know that. I want to emphasize that both

sides had a different set of problems. If there was a conspiracy, the problem

was not rumors of conspiracy. The problem was rumors. Everything had to be gone

into.(7)

(9) On November 25, 1963--the same date as the Katzenbach memorandum President

Johnson directed the Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of

Investigation of all the circumstances surrounding the brutal assassination of

of President Kennedy and the murder of his alleged assassin." (8)

(10) Then, 2 days later, Senator Everett M. Dirksen proposed in Congress that

the Senate Judiciary Committee conduct a full investigation. Congressman Charles

E. Goodell proposed that a joint committee composed of seven Senators and seven

Representatives conduct an inquiry. In addition to the proposed congressional

investigations, Texas Attorney General Waggoner Carr announced that a court of

inquiry, authorized by Texas law, would be established to investigate the

assassination. In his oral history, Leon Jaworski described the creation of the

Texas Court of Inquiry:

I saw Lyndon Johnson within a few days after he assumed the Presidency. Waggoner

Carr had been *** [interruption]*** heard was that naturally the

President--President Johnson--was tremendously concerned over what happened in

Dallas from the standpoint of people understanding

Page 6

6

what really happened. Here and in Europe were all kinds of speculations, you

know that this was an effort to get rid of Kennedy and put Johnson in, and a lot

of other things. So he immediately called on Waggoner Carr who was attorney

general of Texas. Waggoner Carr, follwing President Kennedy's funeral, appeared

on all the networks and made an announcement to that effect.(9)

(11) On November 29, 1963, Walter Jenkins wrote a memorandum to President

Johnson, which stated:

Abe [Fortas] has talked with Katzenbach and Katzenbach has talked with the

Attorney General. They recommend a seven man commission--two Senators, two

Congressmen, the Chief Justice, Allen Dulles, and a retired military man

(general or admiral). Katzenbach is preparing a description of how the

Commission would function***.(10)

(12) This memorandum also included a list of possible members of the Commission

and asked Johnson if they were satisfactory. This list was in fact apparently

satisfactory since all of the people noted were appointed to the Commission.

(13) Former Attorney General Katzenbach told the committee:

I doubted that anybody in the Government, Mr. Hoover or the FBI or myself or the

President or anyone else, could satisfy a lot of foreign opinion that all facts

were being revealed and that the investigation would be complete and conclusive

and without any loose ends.

So, from the beginning, I felt that some kind of commission would be desirable

for that purpose***that it would be desirable *** for the President to appoint

some commission of people who had international and domestic public stature and

reputation for integrity that would review all of the investigations and direct

any further investigation.(11)

(14) On the same day, President Johnson told Hoover that, although he wanted to

"get by" on just the FBI report, the only way to stop the "rash of

investigations" was to appoint a high-level committee to evaluate the

report.(12) That afternoon President Johnson met with Chief Justice Earl Warren

and persuaded him to be chairman of a commission to investigate the

assassination. Johnson explained his choice of Warren by stating,"*** I felt

that we needed a Republican chairman whose judicial ability and fairness were

unquestioned."(13) Although Warren had previously sent word through a third

party that he opposed his appointment as chairman,(14) President Johnson

persuaded him to serve. In "The Vantage Point," President Johnson stated he told

Warren:

When this country is confronted with threatening divisions and suspicions, I

said, and its foundation is being ricked, and the President of the United States

says that you are the only man who can handle the matter, you won't say "no"

will you?(15)

Page 7

7

(15) In his memoirs, Earl Warren stated that on November 29, 1963, Katzenbach

and Solicitor General Archibald Cox met with him and attempted to persuade him

to chair the Commission. Warren refused. He related:

***about 3:30 that same afternoon I received a call from the White House asking

if I could come to see the President and saying that it was quite urgent. I, of

course, said I would do so and very soon therafter I went to his office. I was

ushered in and, with only the two of us in the room, he told me of his proposal.

He said he was concerned about the wild stories and rumors that were arousing

not only our own people but people in other parts of the world. He said that

because Oswald had been murdered, there could be no trial emanating from the

assassination of President Kennedy, and that unless the facts were explored

objectively and conclusions reached that would be respected by the public, it

would always remain an open wound with ominous potential. He added that several

congressional committees and Texas local and State authorities were

contemplating public investigations with television coverage which would compete

with each other for public attention, and in the end leave the people more

bewildered and emotional than at present. He said he was satisfied that if he

appointed a bipartisan Presidential Commission to investigate that facts

impartially and report them to a troubled Nation that the people would accept

its findings. He told me that he had made up his mind as to the other members,

that he has communicated with them, and that they would serve if I would accept

the chairmanship. He then named them to me. I then told the President my reasons

for not being available for the chairmanship. He replied, "You were a soldier in

World War I, but there was nothing you could do in that uniform comparable to

what you can do for your country in this hour of trouble." He then told me how

serious were the rumors floating around the world. The gravity of the situation

was such that it might lead us into war, he said, and, if so, it might be a

nuclear war. He went on to tell me that he had just talked to Defense Secretary

Robert McNamara, who had advised him that the first nuclear strike against us

might cause the loss of 40 million people.

I then said, "Mr. President, if the situation is that serious, my personal views

do not count. I will do it." He thanked me, and I left the White House.(16)

(16) In his oral history, Warren related a similar version of the meeting.(17)

(17) In his appearance before the committee, former President and Commission

member Gerald R. Ford, also recalled the appointment of Chief Justice Warren as

chairman. He testified:

I believe that Chief Justice Warren accepted the assignment from President

Johnson for precisely the same reason that the other six of us did. We ere asked

by the President to undertake this responsibilty, as a public duty and service,

Page 8

8

and despite the reluctance of all of us to add to our then burden or operations

we accepted, and I am sure that was the personal reaction and feeling of the

Chief Justice.(18)

(18) In "The Vantage Point", President Johnson presented two considerations he

had at the time. He believed the investigation of the assassination should not

be done by an agency of the executive branch. He stated, "The Commission had to

be composed of men who were beyond pressure and above suspicion."(19) His second

consideration was that the investigation was too large an issue for the Texas

authorities to handle alone.(20)

(19) Apparently, Earl Warren also did not want Texas to conduct the court of

inquiry that had been announced earlier by Texas Attorney General Waggoner Carr.

In his oral history, Leon Jaworski discussed Warren's attitudes and actions

regarding the court of inquiry:

I came on to Houston, and then I began to get calls from Katzenbach and from Abe

Fortas telling me that they were having a Presidential Commission appointed to

go into this matter. This would be to keep Congress from setting up a bunch of

committees and going in and maybe having a McCarthy hearing or something like

that. The next thing I knew they were telling me, "Leon, you've got to come up

here." This was Katzenbach and Fortas both. "Because the Chief (Chief Justice

Warren, who had accepted the appointment from the President) doesn't want any

part of the court of inquiry in Texas. And I said, "Well, as far as I can see

it, there's no need in our doing anything that conflicts-- let's work together."

He said, "Well, he doesn't want any part of Waggoner Carr, the attorney general

down there, because he said it would just be a political matter." He said, "He

respects you and so***

In and event I then went up to Washington, and I had the problem of working this

matter out. I must say that Deputy Attorney General Katzenbach was a great help;

Solicitor General Archie Cox was of great help. Those two promarily and Waggoner

Carr and I worked with them--Katzenbach saw the Chief Justice from time to time,

bringing proposals to him from me; the Chief Justice was willing to talk to me

without Carr present--I could'nt do that. It finally evolved that--from all

these discussions, there finally evolved a solution that we would all meet. We

did meet in the Chief's office, and the Chief addressed all his remarks to me

and ignored Waggoner Carr, but I would in turn talk to Carr in his presense and

direct the question to him and so on. What we did is agree that we would not

begin and court inquiry, but that we would be invited into hearings; would have

full access to everything.(21)

(20) After this meeting, Leon Jaworski related to President Johnson that the

matter of the Texas court of inquiry had been resolved

Page 9

9

satisfactorily. The President appeared to have been pleased with the result.

Jaworski stated:

When we got through with that, I called Walter Jenkins and told him that we

thought we had solved it properly, and that I ought to have a word with the

President. He said, "By all means. The President is waiting to hear from

you."*** I went on over there and he was in the pool; he came immediately to the

edge of the pool and shook hands with me. Then I told him what had happened, and

that we had worked it out and had worked it out in great shape, and we were

going to work together, and everybody was happy and shook hands and patted each

other on the back and so on. And that even the Chief Justice had warmed up to

Waggoner Carr before the conference broke up. Then Lyndon Johnson looked at me

and he said, "Now, Leon, you've done several things for me--many things in fact

for me. Now, it's my time to do something for you." I said, Mr. President, there

is nothing I want. I don't want you to do anything for me." And so he looked at

me and he said, "All right, I'll just send you a Christmas card then."(22)

(21) On the evening of November 29, 1963, President Johnson issued Executive

Order No. 11130 that created the President's Commission on the Assassination of

President Kennedy, hereinafter the Warren Commission. The Commission was

composed of seven people:

Hale Boggs--Democratic Representative from Louisiana;

John Sherman Cooper--Republican Senator from Kentucky, former Ambassador to

India;

Allen W. Dulles--former Director of the CIA;

Gerald R. Ford--Republican Representative from Michigan;

John J McCloy--former U.S. High Commissioner for Germany and former president of

the World Bank;

Richard B. Russell--Democratic Senator from Georgia, and Earl Warren, Chief

Justice of the Supreme Court.

PURPOSE OF THE WARREN COMMISSION

(22) The purpose of the Warren Commission, as stated in Executive Order No.

11130, were:

To examine the evidence developed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and any

additional evidence that may hereafter come to light or be uncovered by Federal

or State authorities; to make such further investigation as the Commission finds

desirable; to evaluate all the facts and circumstances surrounding such

assassination, including the subsequent violent death of the man charged with

the assassination, and to report to me its findings and conclusions.

(23) Although this may be an accurate statement of some of the purposes of the

Warren Commission, there were indications that there wee additional tasks that

it was to perform.

(24) It is apparent from some of the statements previously quoted that many

members of Government were concerned about convincing

Page 10

10

the public that Oswald was the assassin and that he acted alone.(23) In addition

to the memoranda, referred to earlier, on December 9, 1963, Katzenbach wrote

each member of the Warren Commission recommending that the Commission

immediately issue a press release stating that the FBI report, which had been

submitted to the Warren Commission that same day, clearly showed there was no

international conspiracy and that Oswald was a loner.(24)

(25) The Commission did not issue the requested press release. Although in their

testimony several of the Warren Commission staff members indicated they were not

aware of these memoranda, (25) it is apparent that this purpose was clearly in

the minds of some of the people who were in contact with the Warren Commission

and the members of the Warren Commission could not have been unaware of the

pressure.

(26) Another purpose of the Warren Commission, which was at least apparent to

Chief Justice Warren and to President Johnson, was the quashing rumors and

speculation. President Johnson was conserned that the public might believe his

home State of Texas was involved in the assassination. He was also aware of

speculation about Castro's possible participation. President Johnson expressed

his consern in "The Vantage Point":

Now, with Oswald dead, even a wounded Governor could not quell the doubts. In

addition, we were aware of stories that Castro, still smarting over the Bay of

Pigs and only lately accusing us of sending CIA agents into the country to

assassinate him, was the perpetrator of the Oswald assassination plot. These

rumors were another compelling reason that a thorough study had to be made of

the Dallas tragedy at once. Out of the Nation's suspicions, out of the Nation's

need for facts, the Warren Commission was born. [Italic added](26)

(27) On January 20, 1964, at the first staff meeting of the Warren Commission,

Chief Justice Warren discussed the role of the Commission. A memorandum about

this meeting described Warren's statements:

He (Warren) placed emphasis on the importance of quenching rumors, and

precluding further speculation such as that which has surrounded the death of

Lincoln. He emphasized that the Commission had to determine the truth, whatever

that might be.(27)

(28) At this meeting, Warren also informed the staff of the disscussion he had

had with President Johnson, including the fact that the rumors could lead to a

nuclear war which would cost 40 million lives. (28) Both the Chief Justice and

President Johnson were obviously concerned about the rumors were not quashed.

(29) World reaction to the assassination, and its coverage in the media, may

have reinforced this concern. An editorial on November 23, 1963, in the New York

Times stated that President Johnson "must convince the country that this bitter

tragedy will not divert us from

Page 11

11

our proclaimed purposes or check our forward movement." On November 24, 1963,

the New York Times reported that Pravda was charging right-wingers in the United

States of trying to use the assassination of President Kennedy to stir up

anti-Soviet and anti-Cuban hysteria. The same article stated:

The Moscow radio said Oswald was charged with Mr. Kennedy's slaying after 10

hours of interrogation, but there was no evidence which could prove this

accusation.

(30) On November 25, 1963, Donald Wilson, acting director of the United States

Information Agency, submitted a memorandum to Bill Moyers that discussed world

reaction to Oswald's slaying. This memorandum went through each major city and

summarized newspaper articles that had appeared regarding Oswald's death. A Tass

dispath released after Oswald was killed concluded:

All the circumstances of President Kennedy's tragic death allow one to assume

that this murder was planned and carried out by the ultrarightwing, fascist, and

racist circles, by those who carried out by those who cannot stomach any step

aimed at the easing of international tensions, and the improvement of

Soviet-American relations.(29)

(31) On the same day, the New York Times stated in an editorial:

The full story of the assassination and its stunning sequel must be placed

before the American people and the world in a responsible way by a responsible

source of the U.S. Government *** The killing of the accused assassin does not

close the books on the case. In fact, it raises questions which must be answered

if we are ever to fathom the depths of the President's terrible death and its

aftermath. An objective Federal commission, if necessary, with Members of

Congress included, must be appraised of all and tell us all. Much as we would

like to obliterate from memory the most disgraceful weekend in our history, a

clear explanation must be forthcoming. Not in a spirit of vengeance, not to

cover up, but for the sake of information and justice to restore respect for

law.(30)

(32) An editorial in the Washington Post stated:

President Lyndon Johnson has widely recognized that energetic steps must be

taken to prevent a repetition of the dreadful era of rumor and gossip that

followed the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. A century has hardly

sufficed to quiet the doubts that arose in the wake of that tragedy.(31)

(33) On November 27, 1963, the New York Times reported a Tass dispatch that

severly criticized the Dallas police. On the same day the Washington Post

reported that Castro had accused American reactionaries of plotting the

assassination to implicate Cuba. The Times also reported that the general

feeling in India was that Oswald had been a "tool" and silenced

Page 12

12

by "enemies of peace." (32) Throughout the world, identical sentiments were

being voiced, probably impressing Johnson with the fact that something had to be

done.

(34) The Testimony of several staff members of the Warren Commission supported

the conclusion that the Warren Commission had multiple purposes. Staff members

testified that the purpose of the Warren Commission was to ascertain the facts

of the assassination and to submit a report to the American people.(33) The

staff was however, also aware of Chief Justice Warren's fellings. Staff counsel

David Slawson stated:

His [Warren's] idea was that the principal function of the Warren Commission was

to allay doubts if possible. You know, possible in the sense of being

honest.(34)

Staff counsel Arlen Specter described his reaction to Warren's concern about

rumors by stating:

*** that was a matter in our minds but we did not tailor our findings to

accommodate any interest other than the truth.(35)

Staff consel Norman Redlich believed that the objective of allaying public fears

was "a byproduct of the principal objective which was to discover all the

facts."(36)

(35) While their statements reflected that staff members were concerned with

getting at the truth, there was an additional motive for finding the truth.

Staff consel Bert Griffin stated:

I think that it is fair to say, and certainly reflects my feeling, and it was

certainly the feeling that I had of all my collegues that we were determined, if

we could find something that showed that there had been sommething sinister

beyond what appeared to have gone on.*** (37)

Slawson stated:

I think it is hard to remember 13 years ago what the timing of all these things

was but among the staff members themselves, like when I talked to Jem Liebeler

and Dave Belin and Bert Griffin particularly we would sometimes speculate at to

what would happen if we got firm evidence that pointed to some very high

official. It sounds perhaps silly in retrospect to say it but there was even

rumors at the time, of course, that President Johnson was involved. Of course,

that would present a kind of frightening prospect, because if the President or

anyone that high up was indeed involved, they clearly were not going to allow

someone like us to bring out the truth if they could stop us. The gist of it was

that no one questioned the fact that we would still have to bring it out and

would do our best to bring out just whatever the truth was. The only question in

our mind was if we came upon such evidence that was at all credible how would we

be able to protect it an bring it to the proper authorities? (38)

Page 13

13

(36) Although the staff members' promary concern was the truth, the memers of

the Warren Commission, and not the members of its staff, were the final

decisionmakers with regard to what exactly went into the report. There was some

testimony that indicated Earl Warren's concern about rumors did affect the

writing of the report. When asked why some statements were made that were more

definitive than the evidence, Slawson stated:

I think because Earl Warren adamant almost that the Commission would make up its

mind on what it thought was the truth and then they would state it as much

without qualification as they could. He wanted to lay at rest, doubts. He made

no secret of this on the staff. It was consistent with his philosophy as a

judge.(39)

Slawson also stated:

I suppose he did not think that an official document like this ought to read at

all, tentatively, it should not be a source of public speculation if he could

possibly avoid it. (40)

(37) Staff counsel Wesley J. Liebeler, when asked about some of his critical

memoranda that he wrote regarding the galley proof of the final report, stated:

I think also part of the problem was, as I said before, a tendency, at least in

the galleys of chapter IV, to try and downplay or not give equal emphasis to

contrary evidence and just simply admit and state openly that there is a

conflict in the testimony and the evidence the Commission could conclude

whatever the Commission could conclude. (41)

Liebeler also stated:

Once you conclude on the basis of evidence we had that Oswald was the assassin,

for example, taking that issue first, then obviously it is in the interest of

the Commission, and I presume everyone else, to express that conclusion in a

straightforward and convincing way.***(42)

(38) Former President Ford stated that there were in fact differences between

the proposed language of the report's conclusions as drafted by the staff and

what the Commission finally approved. Ford recalled that one such difference

pertained to the wording of the Commission's conclusion about possible

conspiracy:

There was a recommendation, as I recall, from the staff that could be summarized

this way. No. 1, Lee Harvey Oswald was the assassin.

No.2, the Commission has found no evidence of a conspiracy, foreign or domestic.

The Commission, after looking at this suggested language from the staff decided

unanimously that the wording should be much like this, and I am not quoting

precisely from the Commission staff, but I am quoting the substance:

No. 1, that Lee Harvey Oswald was the assassin. No. 2, the Commission has found

no evidence of a conspiracy, foreign or domestic.

Page 14

14

The second point is quite different from the language which was recommended by

the staff. I think the Commission was right to make that revision and I stand by

it today.(43)

(39) In his appearance before the committee, former Commission member John J.

McCloy stated that he had come to hold a different belief regarding the

possibilty of a conspiracy than he had at the time of the Commission's probe in

1964. He stated that he had come to believe there was in fact some evidence

outweighed the Commission's conclusion. McCloy said:

Insofar as the conspiracy issue is concerned, there hs been so much talk about

that. I don't think I need to dwell on it any longer. I no longer feel we had no

credible evidence or reliable evidence in regard to a conspiracy, but I rather

think the weight of evidence was against the existence of a conspiracy (44)

(40) The late Senator Richard B. Russell, the senior member of the Warren

Commission selected from the Congress, voiced much stronger feelings regarding

the possibility of conspiracy before his death in early 1971. In a television

interview reported by the Washington Post January 19, 1970, he stated that he

had come to believe that there had in fact been a conspiracy behind the

President's murder. With respect to Lee Harvey Oswald, Senator Russell stated,

"I think someone else worked with him." He also stated that there were "too many

things" regarding such areas as Oswald's trip to Mexico City, as well as his

associations, that "caused me to doubt that he planned it all by himself."

Russel believed the Warren Commission had been wrong in concluding that Oswald

acted alone.

(41) J. Lee Rankin, the Commission's general counsel, recalled that toward the

end of the Commission's investigation, he encountered serious difficulty in the

process of coordinating the staff's writing of the report:

The one factor that I did not examine with regard to the staff as much as I

would from my having had this experience was their ability to write and most of

them had demonstrated a considerable ability to write and most of them had

demonstrated a considerable ability to write in Law Review or other legal

materials by their record but my experience taught me that some people are

fluent in writing and others while they are skilled at it have great difficulty

in getting started and finishing and getting the job completed. I don't know

just how I would have tried to have anticapated that problem and worked it out

but it became a serious difficulty for me in my work as general counsel. Looking

back on it I would have much preferred that I had not only all the skills that I

did in the staff but the additional one that as soon as we had completed the

investigation they would go right to work and write a fine piece in which they

described their activities and the results.(45)

(42) Although the Executive order authorized the Warren Commission to conduct

further investigations if the Commission found it desirable,

Page 15

15

Chief Justice Warren did not believe further investigation beyond what the

investigative agencies had provided would be needed. He stated at the first

execution session of the Warren Commission:

Now I think our job here is essentially one for the evaluation of evidence as

distinguished from being one of gathering evidence, and I believe at the outset

at least we can start with the premise that we can rely upon the reports of the

various agencies that have been engaged in investigation of the matter, the FBI,

the Secret Service, and others that I may know about at the present time.(46)

In fact, the Warren Commission did rely extensivly on the investigative agencies

rather than pursuing an independent investigation. (The effects of this reliance

is discussed in another section of this report.)

(43) The evidence indecated, therefore, that the Warren Commission not only had

as its purposes those stated in the Executive order but it also had additional

purposes that may have affected the conduct of the investigation and the final

conclusions. The desire to establish Oswald's guilt and thus to quash rumors of

a conspiracy may have had additional effects on the functioning and conclusions

of the Warren Commission.

ORGANIZATION OF THE WARREN COMMISSION

(44) The Warren Commission investigation was divided into six areas, with two

attorneys assigned to each. Area I was "Basic Facts of the Assassination";

Francis Adams and Arlen Specter were the two lawyers were Joseph Ball and David

Belin. Area III was "Lee Harvey Oswald's Background" to be handled by Albert

Jenner and Wesley J. Liebeler Area IV, "Possible Conspiratorial Relationships"

was given to William Coleman and W. David Slawson. Area V was "Oswald's Death,"

and Leon Hubert and Burt Griffin were assigned to it. Area VI was "Presidential

Protectin." Samuel Stern was assigned was assigned to this area. The General

Counsel of the Commission, Lee J. Rankin, was to assist Stern. Norman Redlich

worked on special projects. He drafted the procedural rules for the Commission,

prepared for the Marina Oswald testimony, and worked with Ball, Belin and

Specter on the investigation of the assassination itself. He also attended as

many Commission hearings as possible and reviewed and edited the drafts of the

report. Howard Willens assisted Rankin in organizing the work, staffing the

Commission, reviewing the materials received from the investigative agencies,

and requesting further information where necessary.

(45) The organization of the Warren Commission staff is important because it, in

fact, determined the focus of the investigation. Four of the areas (I, II, III,

and IV) were concerned primarily with Oswald--his activities on November 22,

1963, and his background. Only one area, representing one-sixth of the available

personnel, was devoted to the investigation of Ruby's role. This area was also

framed in terms

Page 16

16

of Oswald--it was called "Lee Harvey Oswald's Death." No area specifically

focused on the investigation of pro- or anti-Castro Cuban involvement, organized

crime participation, or even the investigative agencies' role in the

assassination. The area of domestic conspiracy was considered as part of Area

III, "Lee Harvey Oswald's Background," which again focused the issue of

conspiracy on Oswald.

(46) Former President Ford testified that he had been critical of Chairman

Warren's selecting a general counsel without first consulting the other members

of the Commission. Ford stated that he beieved Warren was attempting to place

too much control over the Commission in his own hands:

After my appointment to the Commission, and following several of the

Commission's organizational meetings, I was disturbed that the chairman, in

selecting a general counsel for the staff, appeared to be moving in the

direction of a one-man commission. My views were shared by several other members

of the Commission.

The problem was resolved by an agreement that all top staff appointments would

be approved by the Commission as a whole.(47)

(47) In his testimony, Howard Willens explained the rationale for the

organization of the staff:

I believe the rationale is readily stated. In order to begin and undertake a

project of this dimension, there has to be some arbitrary allocation of

responsibilities. There is no way to do it that eliminates overlap or possible

confusion but this was an effort to try to organize the work in such a way that

assignments would be reasonable clear, overlaps could be readily identified, and

coordination would would be accomplished among the various members of the

staff.(48)

(48) The staff members who testified before the committee generally believed the

organization was effective. Specter stated, "Yes, I think the categories were

adequate to finding the truth."(49) Redlich said, "The procedures and the

organization were an important part in introducing the end result which I

thought was professional and thorough investigation of the assassination."(50)

Only Griffin expressed dissatisfaction with the organizational structure:

GRIFFIN. As far as I was concerned, I did not feel that it operated in a way I

felt comfortable.

STAFF COUNSEL. How would you have done it differently?

GRIFFEN. Let me first of all preface it Hubert and I began to feel after a

couple of months that perphaps there was not a great deal of interest in what we

were doing, that they looked upon the Ruby activity, based upon information that

they saw as being largely peripheral to the questions that they were concerned

with. We did have a disagreement, pretty clear disagreement, on how to go about

conducting the investigation and I think that again was another reason why

perhaps I would say the operation was not as effective as I would have liked to

have seen it (51)

Page 17

17

(49) The pay records of the Warren Commission staff indicate that several of the

senior attorneys did not spend much time working on the investigation, and the

testimony of staff members supported this fact. Arlen Specter stated:

I would prefer not to ascribe reasons but simply to say some of the senior

counsel did not participate as extensively as some of the junior counsel. (52)

He added:

It is more accurate to say I ended up as the only counsel in my area.(53)

(50) When asked if the senior cousels devoted much time to the investigation,

Slawson stated:

A few did not. The majority of them did--and I think contributed very valuably.

They did not, with a couple of exceptions, spend as much time as the younger men

did, especially as the investigation wore on. Some of them, I understand, were

hired with the promise that turned out not to be the case.(54)

(51) Howard Willens stated, when asked about the accuracy of the chart

describing the pay records:

I think in the roughest terms this gives a fair picture of the days spent during

the period by members of the staff. I think that with reference to my earlier

comment you should note that several of the senior counsel felt that their

primary responsibility was to work in the investigative stages of the

Commission's work.(55)

(52) The failure of the senior attorneys to participate fully is attributed to

the impression they had that their role on the Commission did not require their

working full time and that their participation would only be needed for 3 to 6

months. Griffen supplied another reason for at least one senior cousel's leaving

early:

A third reason was, however, that Hubert was disenchanted with some of the

things that were going on in that he didn't feel he was getting the kind of

support that he wanted to get, and he expressed to me a certain amount of

demoralization over what he felt was unresponsiveness that existed between

himself and particulary Mr. Rankin.(56)

(53) Some of the staff members testified that the staff were qualified people

and that there were a sufficient number of lawyers to conduct the investigation.

The testimony also indicates, however, that there was some dissatisfaction and

that the failure to work full time on the part of the senior counsels probably

affected the investigation. When Redlich was asked if the staff, not

participating full time affected the work, he stated:

Any time someone is not able to spend full time it had that effect. It means

that that work which might have been done during the course of that full-time

work gets picked up by

Page 18

18

others *** I don't think on balance any of that had a permanent harmful effect

because I believe that the entire staff taken as a whole, managed to conduct

what I consider to be a thorough inquiry. Obviously, as anyone who has conducted

an investigation knows, you always would like to have everyone there all the

time. That was not possible during a substanntial portion of the Warren

investigation.(57)

(54) Slawson responded to the same question:

As I said before, I felt overworked and I think many of the staff members felt

the same way. I think the main problem was one of the great underestimation of

the size of the task at the time. As I said, we were told, we were telephoned

and asked to come in; it would be 3 to 6 months. It is my recollection they said

it would be only 3 to 6 months on the outside and of course we ended up taking

about 8. There was a reluctance, once we were there, to admit--again this is a

matter of once you have made a decision you don't like to admit you were

wrong--but people did not like to admit that we probably needed more help and

more time.(58)

(55) The pay records indicated that from the diddle of January to the end of

September, Francis Adams, a Commission counsel, worked a total of 16 8-hour days

and 5 additional hours. Adams held one of the single most important positions

with the Commission, serving as senior attorney in the area of basic facts of

the assassination. Arlen Specter, when asked if this affected his performance,

stated:

I don't think it did although it would have been helpful if my senior counsel,

Francis Adams, had an oppurtunity to participate more extensively.(59)

(56) J. Lee Rankin told the committee:

There is one member that you can see that did not attend hardly at all and I

certainly should have gotten rid of him really.*** That was Francis Adams and he

really didn't contribute anything.(60)

(57) Lieber also indicated he did not work closely with the senior attorney in

his area, Albert Jenner. He stated:

My recollection is that during the early part of the Commission's work that Mr.

Jenner was concerned, I believe he was interested in becoming president of the

American Bar Association and I believe he spent some time on that issue.(61)

(58) While describing the organization of the work in his area, Liebeler stated:

It was difficult for Mr. Jenner and me to work out a general relationship on

that question at that time. Since I was a so-called junior staff member at that

time, Mr. Jenner was not, I was quite unsure when I started as to how to handle

the problem. I finally just decided to do my own thing and basically went ahead

and did most of that original work, myself. Mr. Jenner and I never actually

worked very closely together. He worked on projects and I worked on

projects.(62)

Page 19

19

INDEPENDENT INVESTIGATORS

(59) As stated earlier, the Warren Commission staff was primarily composed of

attorneys, with a few assistants drawn from other agencies of the Government. It

had no independent investigators, but relied primarily upon Government agencies

to supply leads and perform a large majority of the field investigation.

(60) The Commission's former general counsel, J. Lee Rankin, told the committee

that he believed it would have been difficult to assemble an independent

investigative staff. Rankin recalled:

Well, I gave some thought to that and I finally conluded that I would lose more

than I would gain, that the whole intelligence community in the Government would

feel that the Commission was indicating a lack of confidence in them and that

from then on I would not have any cooperation from them; they would universally

be against the Commission and try to trip us up.(63)

(61) J. Lee Rankin told the committee that the decision not ot have the

Commission employ its own investigators:

* * * was a decision of the Commission, although I recommended that kind of a

procedure because I described various possibilities of getting outside

investigators and that it might take a long period of time to accumulate them,

find out what their expertise was, and whether they could qualify to handle

sensitive information in the Government, and it might be a very long time before

we could even get a staff going that could work on the matter, let alone have

any progress on it.(64)

(62) Slawson stated:

We had special people assigned from CIA, FBI, and Secret Service who were with

us more or less full time, especially the Secret Service who were

investigators.(65)

(63) There was one indication that the Warren Commission used some independent

experts for the examination of the physical evidence. Slawson stated:

I think that some of the areas of investigation such as that headed by Dave

Belin, which was the immediate circumstances of the shooting in Dallas, employed

private investigators at various points to cross-check and give an independent

evaluation.(66)

(64) Redlich stated:

My recollection is that in ballistics I believe we used someone from the

government of Illinois, either handwriting or fingerprinting. I am not sure it

was not someone from the New York City Police Department.(67)

(65) There was also some indication that the staff would have preferred to have

had independent investigators. Spector said:

If [in] organizational structure you include the personnel available, I think

that everyone would have much preferred to

Page 20

20

have had a totally independent investigative arm to carry out the investigative

functions of the Commission, but I believe the Commission concluded early on,

and I was not privy to any such position from my position as assistant counsel,

that it would be impractical to organize an entire investigative staff from the

start so that use was made of existing Federal investigative facilities * * *

there would be an observation [among the staff] from time to time how nice it

would be if we had a totally independent staff.(68)

(66) When asked if any consideration was given to hiring independent

investigators, Redlich replied:

I have no clear recollection of that. Certainly during the time of the

investigation from time to time staff members talked to Mr. Rankin about what it

might have been like if we had had a completely independent staff. I think that

we reached the conclusion then, with which I still agree, that while using the

existing investigatory arms of the United States had certain disadvantages, on

balance it was still the right decision to make. There were certain tradeoffs

*** I don't think there was any happy, completely happy solution to that

dilemma.(69)

(67) John McCloy stated that he did not believe the Commission suffered from an

insufficient investigative capacity:

* * * it is not true we didn't have our own investigative possibilities. There

was a very distinguished group of litigating lawyers [on staff] that we called

on *** We had a very impressive list and they did great work. So it is not true

we relied entirely on the agencies of the Goverment.(70)

(68) Former President Ford told the committee that he believed the Commission's

decision not to employ an investagative staff was correct:

It is my best judgment that the procedure and the policy the Warren Commission

followed was the correct one and I would advocate any subsequent Commission to

follow the same.

For the Warren Commission to have gathered together an experienced

[investigative] staff, to get them qualified to handle classified information,

to establish the organization that would be necessary for a sizable number of

investigators, would have been time-consuming and in my opinion would not have

answered what we were mandated to do.

It is my, it is my strong feelings that what we did was the right way. We were

not captives of, but we utilized the information from the in-house agencies of

the Federal Government * * *.(71)

(69) Ford also told the committee:

The FBI, and I use that as an example, undertook a very extensive investigation.

I don't recall how many agents but they had a massive operation to investigate

everything. The Commission with this group of 14 lawyers and some additional

Page 21

21

staff people, then drew upon all of this information which was available, and

we, if my memory serves me accurately, insisted that the FBI give us everything

they had. Now that is a comprehensive order from the Commission to the Director

and to the FBI. I assume, and I think the Commission assumed, that athat order

was so broad that if they had anything if they had anything it was their

obligation to submit it. Now if they didn't, that is a failure on the part of

the agencies, not on the part of the Commission. (72)

(70) In his testimony, Burt Griffin supplied anther explanation for the

Commission's decision to rely upon the investigative agencies:

* * * there was a concern that this investigation not be conducted in such a way

as to destroy any of the investigative agencies that then existed in the

Government. There was a genuine fear expressed that this could be done. Second,

it was important to keep the confidence of the existing investigative agencies,

and that if we had a staff that was conducting its own investigation, that it

would generate a paranoia in the FBI and the other investigative agencies which

would not only perhaps be politically disadvantageous, it would be bad for the

country because it might not be justified but it might also be

counterproductive. I think there was a fear that we might be undermining *** My

impression is that there was genuine discussion of this at a higher level than

mine.(73)

COMMUNICATION AMONG THE STAFF

(71) The testimony of the staff members indicated that there generally was no

problem of communication among the areas. Specter stated that the information

was "funneled" by Rankin and he had no reason to believe the process was

unsuccessful. (74) Willens described the procedures for facilitating the

exchange of information:

One way of dealing with the separate areas within which the lawyers were dealing

was to make certain that all the materials that came in the office were reviewed

in one central place and that any material that bore even remotely or

potentially on an area. It was frequently the case that materials in our

possession were sent to three or four areas so that each of the groups of

lawyers could look at the same material from that group's perspective and decide

whether it had any relevance in the part of the investigation for which those

lawyers were reponsible. I continued this function throughout the Commission and

always erred on the side of multiple duplication so as to make certain that the

members of the staff in a particular area did get the papers which I thought

they needed. Another way of coordinating among the staff was by the circulation

of summary memoranda, which happened on a regular basis throughout the

Commission's work * * * The third way of coordinating among the staff was

perhaps more informal and related primarily to the ease with which the members

Page 22

22

of the staff could get together to discuss a problem in which more than one area

had particular interest.(75)

(72) Griffin also commented the communication between the staff members:

We had very few staff meetings of a formal nature. We did have two or three,

maybe four or five. The bulk of the communication was on a person-to-person ad

hoc basis. There were some memos, I believe, passed back and forth. (76)

He expressed some dissatisfaction with the communication he and Hubert had with

Rankin:

I suppose that it would not be fair to say that we did not have direct access to

Rankin. I cannot say at any point when we tried to see Rankin that we couldn't

see him. I don't recall any situation where we were formally required to go

through someone else to get there. There was no doorkeeper in a certain sense.

All of those communications that were in writing that went to Rankin went

through Howard Willens, but as a practical matter, and I am not sure entirely

what the reasons are, Hubert and I did not have a lot of communication with

Rankin. We really communicated with him personally infrequently. We had certain

amount of communication at the beginning. I do remember at the outset Hubert and

I had a meeting with Rankin in which we discussed the work of the mission that

we had, but I would say that by the first of April we had relatively little

communication with Rankin. That is, we might not speak to Rankin maybe more that

once every 2 weeks. Mr. Rankin is a formal person. Hubert and I did not feel

comfortable in our relationship with him. I point this out because I think our

relationship with Rankin was different than some of the other staff members. I

think a number of them would genuinely say, and I would believe from what I saw,

that they certainly had much better communication than we did. Whether they

would regard it as satisfactory I don't know.(77)

(73) The staff also indicated that they would communicate informally in the

evenings. Specter stated:

There was a very informal atmosphere on the staff so that there was constant

contact among all the lawyers both during the working day and those of us who

were around the evenings. We would customarily have dinner together, the virtual

sole topic of conversation was what each of us was doing. So there was a very

extensive exchange albeit principally informal among members of the staff as to

what each was doing. (78)

INTERACTION BETWEEN THE WARREN COMMISSION AND THE STAFF

(74) In his testimony, Howard Willens stated that the majority of the

communication between the staffmembers and the Warren Commission members was

through Rankin. Direct contact with members of the Warren Commission was

minimal:

Page 23

23

Apart from those occasional meetings with the Chief Justice most of the staff's

dealings with the members of the Commission occurred on a sporadic and limited

basis.(79)

(75) Norman Redlich stated:

However, in terms of informal relationship between the staff and the Commission

in the sense of the staff being present at the Commission meetings in a formal

way, that did not exist. I was not present at any meeting of the commission. I

was not privy to any formal meetings of the commission. Mr Rankin was the

official line of communication between the Commission and the staff.(80)

(76) Burt Griffin stated:

I had almost a total lack on contact with the Commission members. I have some

thoughts in retrospect now about some of the perceptions, total conjecture but

based on other things that have happened, but at the time I did feel senator

Russell was genuinely concerned about conducting the investigation. (81)

(77) Redlich also indicated that some of the staff were not satisfied with their

relationship with the members of the Warren Commission:

I believe that perhaps some members of the staff would have preferred to have

had a more direct ongoing formal relationship with the Commission. (82)

(78) Arlen Specter described the relationship with the members of the Warren

Commission as "Cordial, somewhat limited." (83)

(79) There is at least one exception to this formal relationship between staff

members and the Commission. W. David Slawson indicated he often met with Allen

Dulles:

Allen Dulles and I became fairly close I think. He had aged quite a bit by the

time he was on the Warren Commission and was also sick. I have forgotten, he had

some kind of disease that made one of his legs and foot very painful. So he was

not effective sometimes but when he was he was very smart and I liked him very

much. Because of my particular assignment of course he spent a lot of time with

me. We talked informally quite a bit. (84)

(80) In spite of this lack of contact between the staff and the Commission

members, some of the staff members believed that the Commissioners were

reasonably well informed and the interaction was satisfactory. Arlen Specter

thought the Commissioner were generally well informed about the facts of the

case. (85) When asked if the Commissioners were informed, Redlich responded:

I think some of them were tremendously well informed. the Chief Justice was

extremely well informed. I believe that former President Ford was extremely well

informed. Mr. Dulles attended a great many hearings. I believe that on the broad

areas of the Commission's inquiry the Commission was informed. They were

obviously not as informed of some

Page 24

24

of the specific enormous factual data in connection with the assassination as

was the staff. I have never known a staff that thought that group that it worked

for was as well informed as the staff was, and the Warren Commission was no

exception. (86)

(81) Wesley Liebeler, discussing a statement he was alleged to have made

regarding the Warren commission, stated:

What I had intended to convey to Mr. Epstein (the author of a book on the

Commission) was the idea that in terms of developing the investigation, the

direction in particular of the investigation, and in drafting the report, the

Commissioners themselves were not directly involved, and they were not. (87)

(82) Despite Liebeler's statement that the commissioners were not involved in

writing the report, the drafts of the report wee in fact circulated among the

Commission members for their review, suggestions and approval. The Commissioners

made comments and criticisms at this point and the drafts wee rewritten to

conform with their desires. (88)

(83) The Warren Commission had no formal sessions from June 23, 1964 to

September 18, 1964. This was the period during which the final report was

written. Had the commissioners participated to a greater extent during the

investigative stages and had they had more interaction with the staff members,

there might have been additional discussion and comments about the content of

the report might have been substantially different. Additional issues might have

arisen. For example, in his testimony, Specter stated:

* * * the Commission made a decision as to what would be done which was not

always in accordance with my own personal view as to what should be done, for

example, the review of the X-rays and photographs of the assassination of

President Kennedy. I thought that they should have been observed by the

Commission and by me among others perhaps having responsibility for that area

and I said so at the time. (89)

(84) John McCloy told the committee that he had also voiced objections over

Chief Justice Warren's decision not to have the commission view and evaluate

these materials during the investigation:

I think we were a little lax in the Commission in connection with the use of

those X-rays. I was rather critical of Justice Warren at that time. I thought he

was a little too sensitive of the sensibilities of the family. He didn't want to

have put into the record some of the photographs and some of the X-rays there.

(90)

(85) During the final stages of the Warren Commission, the Commissioners were

almost evenly divided on the question of whether the single-bullet theory was

valid. To resolve this conflict, the Commissioners had the report worded in such

a way that was no conclusive answer. The report stated:

Page 25

25

Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to

determine just which shot hit Governor Connally, there is very persuasive

evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the

President's throat also caused Governor Connally's wounds. However, Governor

Connally's testimony and certain other factors have given rise to some

difference of opinion as to this probability but there is no question in the

mind of any member of the Commission that all the shots which caused the

President's and Governer Connally's wound were fired from the sixth-floor window

of the Texas School Book Depository. (91)

(86) Of the controversy over the single-bullet theory, John Sherman Cooper

recalled:

We did have disagreements at times in the Commission and, I as I recall, I think

the chief debate grew out of the fact or the question as to whether there were

two shots or three shots or whether the same shot that entered President

Kennedy's neck penetrated the body of Governor Connally.

I must say, to be very honest about it, that I held in my mind during the life

of the Commission that there had been three shots and that a separate shot

struck Governer Connally. (92)

(87) Had the Commissioners been close to the investigation and more aware of the

questions and issues regarding the ballistics evidence, they might have agreed

to examine the photographs and X-rays. Instead, probably because of the time

problem, the issue was resolved by the use of agreeable adjectives, rather than

by further investigation.

PRESSURES

(88) The Warren Commission was created on November 29, 1963. By the end of

January 1964, the staff of the Warren Commission had been completely assembled.

The hearings began on February 3, 1964, and were completed on June 17, 1964. The

summer of 1964 was spent writing and editing the report. On September 24, 1964,

the Warren report was submitted to President Johnson. The Warren Commission,

therefore, lasted a total of 10 months, with approximately 3 to 4 months spent

on the investigation itself and the remaining months, as previously stated, on

writing the report and organizing the staff.

(89) Time and political pressures were much in evidence during the course of the

Warren Commission and may have affected the work of the Commission. While some

staff members testified that there was no time pressure others indicated that

time was a concern and was inextricably combined with political pressures.

(90) There definitely was a desire to be prompt and the complete the

investigation as soon as possible. Specter stated:

* * * The attitude with respect to time perhaps should be viewed in November of

1977 as being somewhat different from 1964 to the extent that the Commission was

interested in a prompt conclusion of its work. It did not seek to sacrifice

completeness for promptness. When the Commission started its job there was no

conclusion date picked. My recollection

Page 26

26

is that it was discussed in terms of perhaps as little as 3 months, perhaps as

much as 6 months. As we moved along in the investigation there were comments on

attitudes that we should be moving along, we should get the investigation

concluded, so that the scope of what we sought to do and the time in which we

sought to do it had as its backdrop an obvious attitude by the Commission that

it wanted to conclude the investigation at the earliest possible date.(93)

(91) Specter also stated:

It is hard to specify the people or Commissioners who were pushing for a prompt

conclusion, but that was an unmistakable aspect of the atmosphere of the

Commission's work.(94)

(92) When asked if there was enough time, Willens responded:

I think the time was sufficient to do the work of the Warren Commission. I

cannot deny that the work could have gone on for another month or two or six.

(95)

(93) In spite of the desire for promptness, Specter and Redlich also believed

there was still enough time to complete their work. (96) At one point in his

testimony, Slawson stated this:

* * * although at times I was afraid there wouldn't be. There was time pressure

on all of us. I think that all members of the staff were bothered and somewhat

resented the fact that we were pushed to work at such a rapid pace, but we

resisted any attempts to make us finish before we felt we were ready to be

finished. When the report came out neither I, and I don't think anybody else,

felt that there was anything significant that we had not been able to do in the

time.*** But the amount of paper that we had to go through to do our job well

was tremendous *** I had so many documents to get through and try to understand

and try to put together. They continued pouring in from the ongoing

investigation after that. There weren't that many of us. So we had more than

enough to do, I would say. (97)

(94) Later, when asked about some of the problems with the footnotes of the

report. Slawson indicated one effect that time pressure had on the work of the

Commission:

I took, and I think everyone else did, as much care as we could. But the time

pressure was severe. With the mass of material that we had I am sure that errors

of numbering, and perhaps what footnote A should have had, footnote B did, and

vice versa, occurred. I don't think that the kind of crosschecking that normally

goes into a good professional publication, for example, ever went into this (98)

(95) Griffin also indicated some concern about the amount of work that had to be

done within the short period of time:

*** But Hubert and I, we had a completely, we had a scope of investigation that

was as great as all the other people put together, because we were investigating

a different

Page 27

27

murder. We had two people who were investigating a conspiracy from one man's

point of view and we had a security question, how did he get into the basement,

and so forth. (99)

(96) In his testimony before the committee, former general counsel J. Lee Rankin

gave his perception of the time factor: